Week One – Passage Of The Cancer Cells

March 10, 2023

My friend Daria frequently complains to me about traffic and her 40-minute (sometimes longer) commute to school. I sympathized, but until I took this internship, I did not truly understand nor appreciate her struggle. My internship, located in Manassas, is 40 minutes away from my house. On Monday I missed the exit back, made another wrong turn onto the exact opposite direction from where I needed to go, exited quickly onto Nutley St, and then spent 30 minutes on side streets and bridges just to avoid the horror of having to navigate the highway again. Highways frighten me, especially during rush hour.

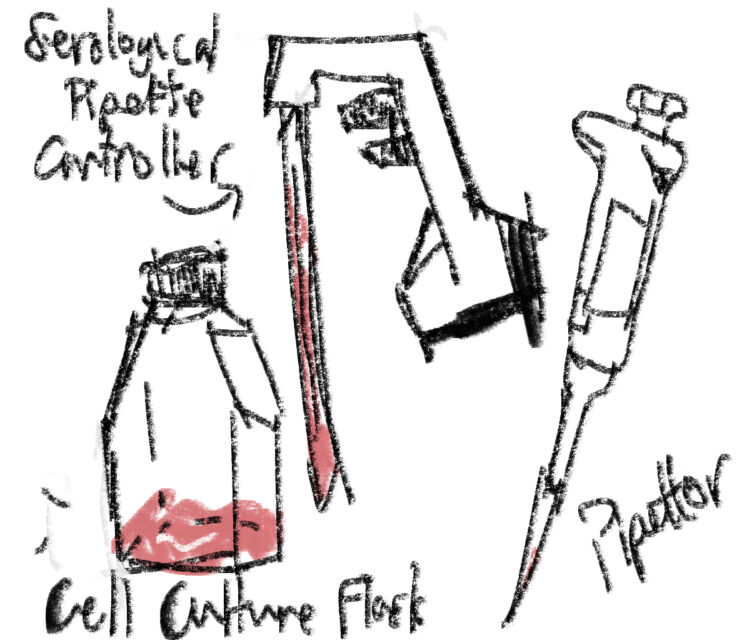

On the flip side, I learned a lot about what scientists do all day by observing Purva, my graduate student mentor. The first day, I watched her passage her cells. Also called subculturing, this procedure basically involves moving the delicate cells, who have already used up the nutrients in their culture media (water-based home) and secreted waste products all over it, into new containers and culture media. But since these specific cells are adherent, meaning they grow in a monolayer over the plastic and specially treated flask bottom, she must add a 0.25% solution of trypsin (a digestive enzyme in vertebrates) in order to dislodge them. Depending on the cell type, she might instead do this mechanically: scrape them off with the equivalent of tiny and very sterile ice scrapers, except the blade is twisted sideways for more efficient scraping inside the relatively small culture flask (what I called “tub-like” last post). Just imagine a bladed toothbrush. Once the cells are dislodged, she must then: add culture medium and centrifuge the solution so the cells collect in a clump at the bottom; re-suspend the pellet (by adding and removing culture media) and remove a sample for counting cell number and determining viability; and dilute the remaining cells to the appropriate seeding density and pipet that into new cell culture vessels, which can be sealed, sprayed with 70% ethanol to sterilize any potential bacteria which may enter or cling, and unceremoniously shoved back in the 37℃, 5% CO2 incubator for the cells to grow for another 2 or 3 days. After which they must be passaged again, until it’s time to analyze them with more… invasive techniques. I think it will take me a while to memorize the passaging procedure. But I will practice with supervision and it will happen! Something that stunned me about lab work: how much waste a properly equipped and properly aseptic laboratory generates. Purva switched and threw away tubes, plastic pipettor tips, glass serological pipettes, and cell-scrapers between most steps, because you any contamination would destroy the purpose of the experiment in the first place. The conservationist in me says no, but the scientist in me says yes.

I realize this is all kind of confusing, so here is a little diagram of some of the stuff I worked with:’

On Thursday, I began a culture of my own cells, some cancerous mouse macrophages. Purva did the bulk work of passaging them, and then I added 10 mL of their media to a tub and then 1 mL of the cells. I have no idea what I’m gonna do with them! The scientists here compare them to babies we have to take care of. Parenthood is hard and confusing!

As for my senior project, I read a bit about cell culture basics and the required materials. Since quality, safety, consistency, and regulatory compliance are key, it seems that a few big corporations provide the basic materials and equipment most labs require (a long list that includes everything from tubes and pipettes to chemical fume hoods and biological safety cabinets). So I think my next step should be to investigate inventorying practices and see what most labs own.

See you next week,

Raleigh ♡