January 9, 2026

Families are often intrigued to learn that the study of Latin as a World Language is an important part of the curriculum at BASIS Independent Bellevue. All students study Latin in grades 5 and 6, building a strong foundation in language, history, and critical thinking. Beginning in grade 7, students may choose their World Language that they intend to take up through the high school level. The World Language choices are Latin, Mandarin, Spanish, or French. Remarkably, when given the choice in grade 7, many students elect to continue their Latin studies. So why Latin?

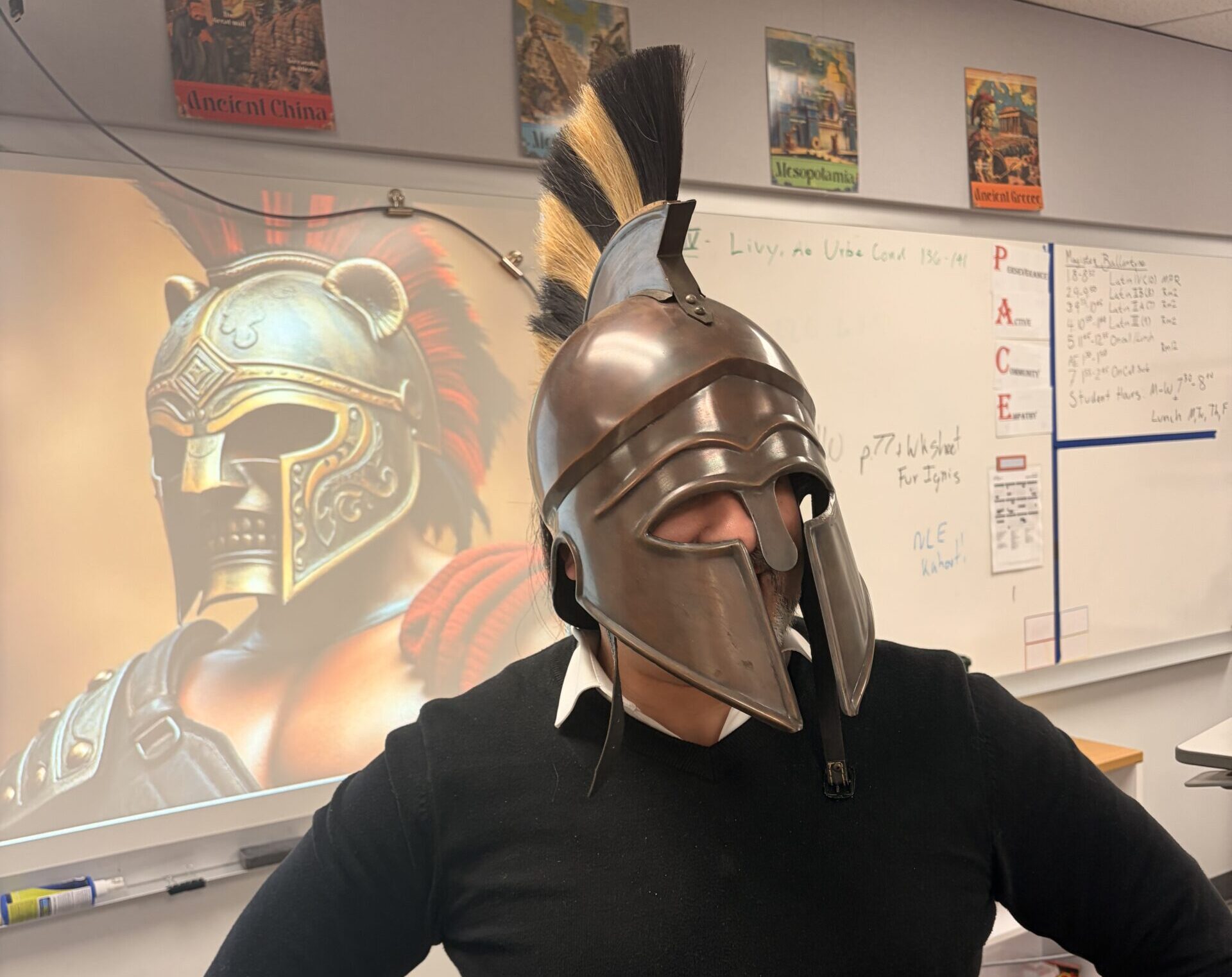

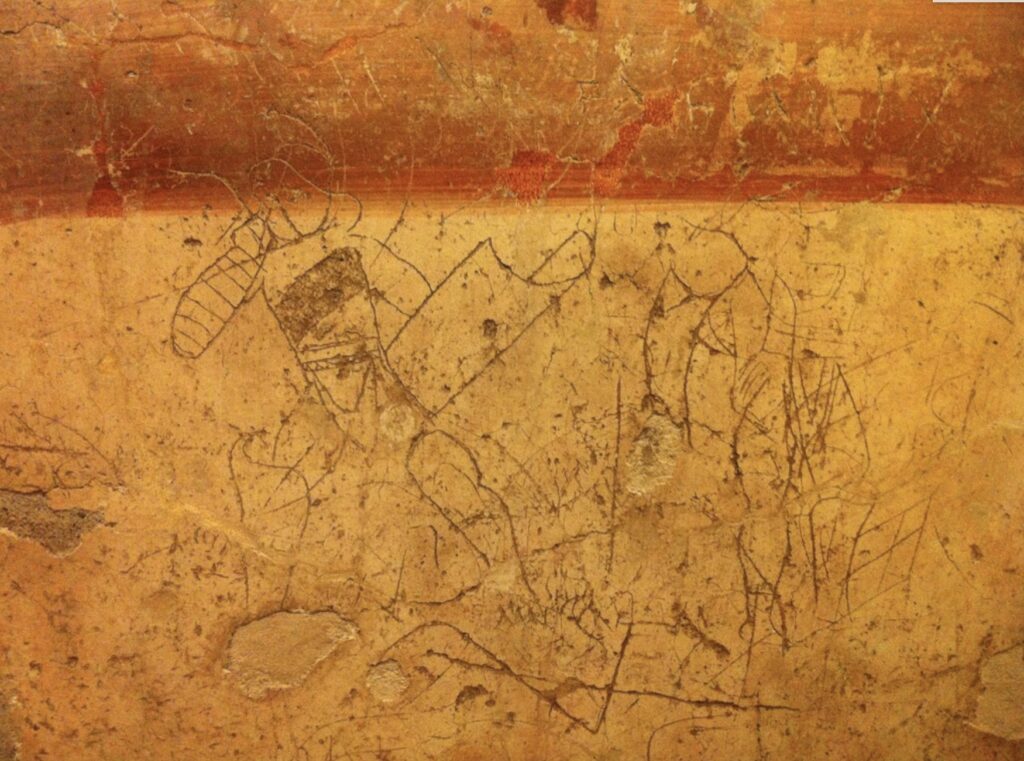

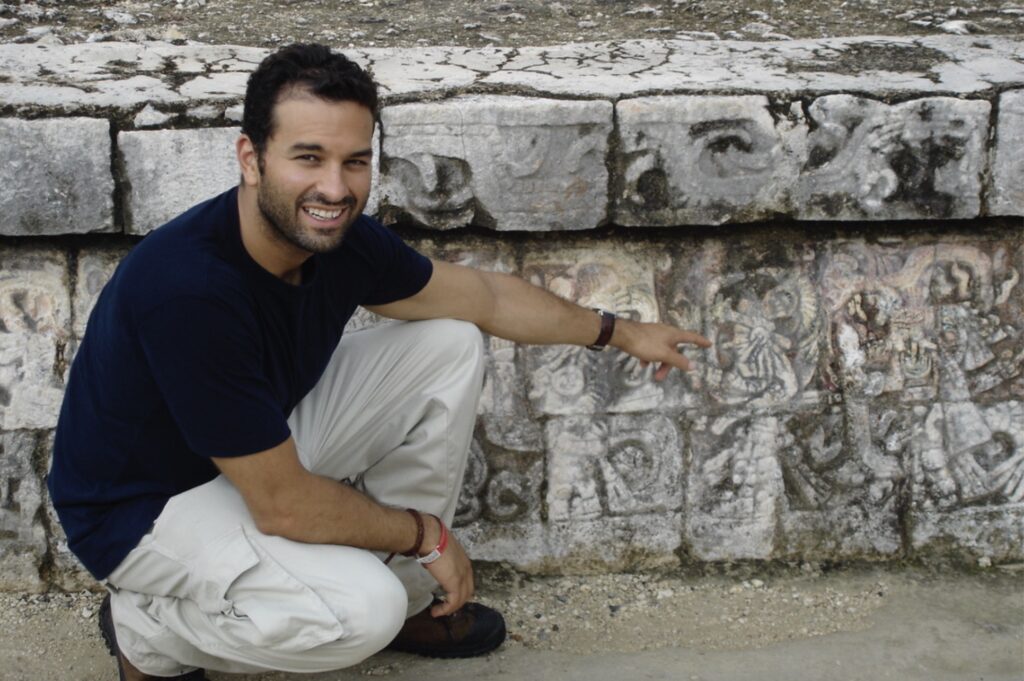

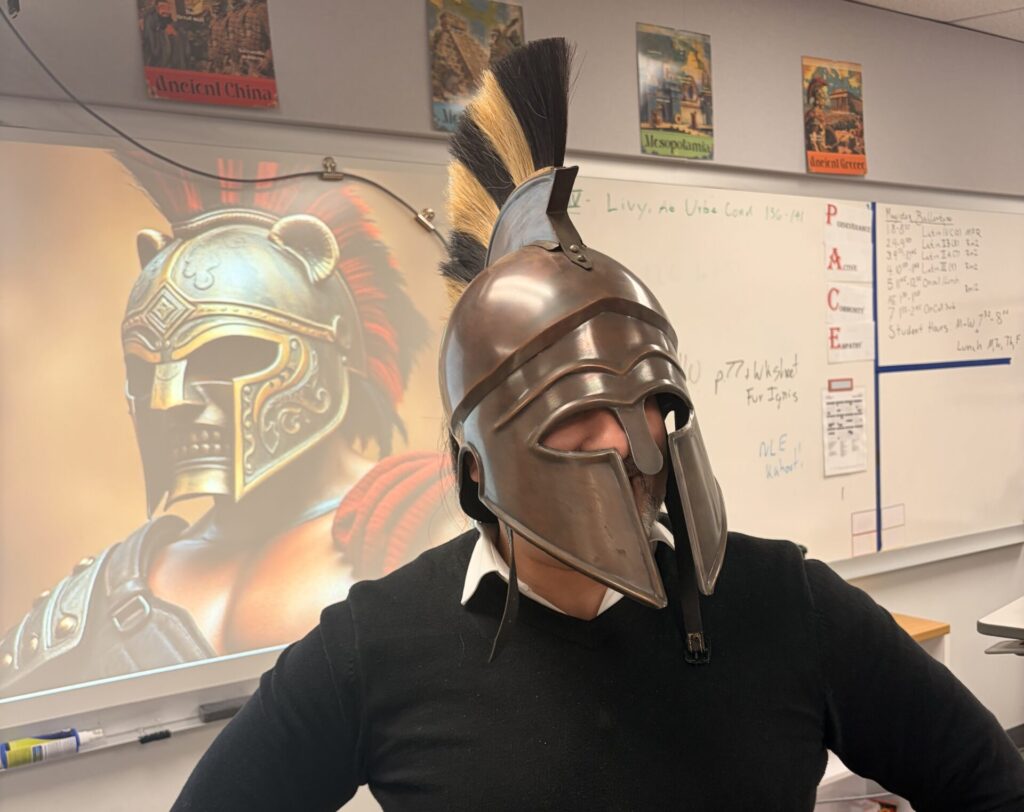

To provide a window into what Latin looks like at BASIS Independent Bellevue, one of our exceptional teachers, Mr. Ballantyne, has agreed to share his experiences with Latin, both inside and outside the classroom. A former professor at Baylor University, Mr. Ballantyne brings over a decade of experience teaching Latin, Roman Archaeology, and Art History at the college and high school levels, including IB and AP Latin. From excavation sites in Pompeii to the classroom at BASIS Independent Bellevue, we invite you to step into his journey with Latin!

Latin Beyond the Classroom with Mr. Ballantyne

When people find out I teach Latin, they often ask, “Why Latin? Isn’t it a dead language?” I usually smile, because Latin has taken me places, I could never have imagined when I first encountered it as a student— ancient cities, museums, excavation trenches, and even crime scenes—Roman ones, at least.

Latin is everywhere, even when we don’t notice it. We hear it in law and medicine, see it in mottos like Ad astra per aspera, “To the stars, through hardship,” and recognize it in popular culture—from Harry Potter spells, like expelliarmus, to the Latin-inspired worlds of Percy Jackson and Star Trek. But what surprised me most was how Latin connects us to ordinary people in the past.

As an archaeologist, I study Roman graffiti—the everyday words scratched onto walls in places like Pompeii. These are not polished speeches or epic poems. They are messages like, “Marcus loves Julia,” advertisements for bakeries, jokes between soldiers, and complaints about bad service. In many ways, they are the ancient equivalent of social media. When students translate them, they realize something powerful: people two thousand years ago worried, joked, loved, and complained just like we do.

Latin has also led me quite literally into the ground at an archaeological dig near Pompeii, where I was a part of an international team of students excavating just beyond the walls of Pompeii. For weeks, we carefully dug and documented the site, expecting to uncover evidence of Roman life. Instead, we found almost nothing. Day after day, trench after trench, the ground remained frustratingly empty.

Then one afternoon, we uncovered a small, broken object: an ivory smoking pipe. It wasn’t Roman at all. At first glance, the pipe didn’t seem important, but it turned out to be the key to understanding the entire site. Pipes weren’t used until the discovery of tobacco in the New World. In fact, it dated to the 1700s, when Pompeii was first explored under Charles VII, the king of Naples.

The pipe told us that people had already been there long before us. In the eighteenth century, Pompeii was often dug not by archaeologists as we know them today, but by treasure hunters working for royalty. They searched for impressive objects to display, removing items without carefully recording where they came from. As a result, many areas were quietly emptied centuries ago.

That broken pipe explained why our excavation felt so puzzling. We weren’t failing to find Roman artifacts, but rather the site had already been picked clean. The emptiness of the ground was itself the evidence. This experience taught us an important lesson: archaeology isn’t just about discovering objects. It’s about uncovering the past, including the stories of people who came before us, even earlier excavators. Sometimes a small, unexpected find can answer bigger questions than a spectacular treasure ever could.

Bringing the Ancient World into the Classroom

As we begin this new academic year, I want my students to feel that same spark of excitement and discovery I felt when I translated my first Latin inscription, coin, or monument. When they conjugate verbs or translate sentences, they’re not only doing grammar drills. They are decoding the voices of a lost world.

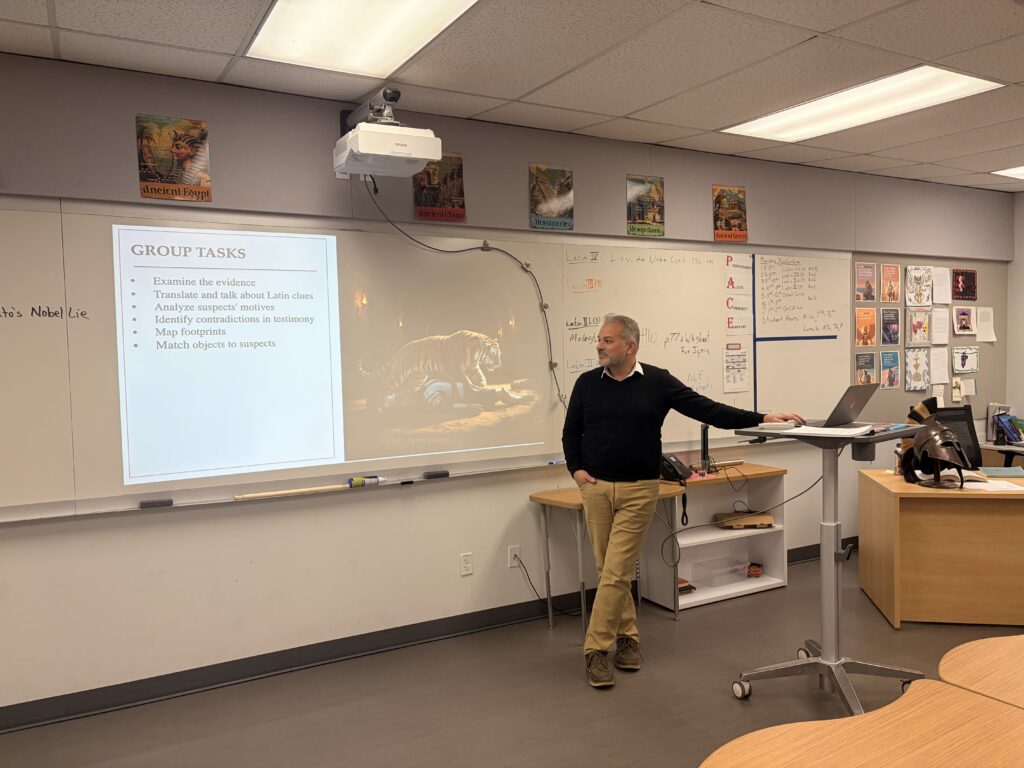

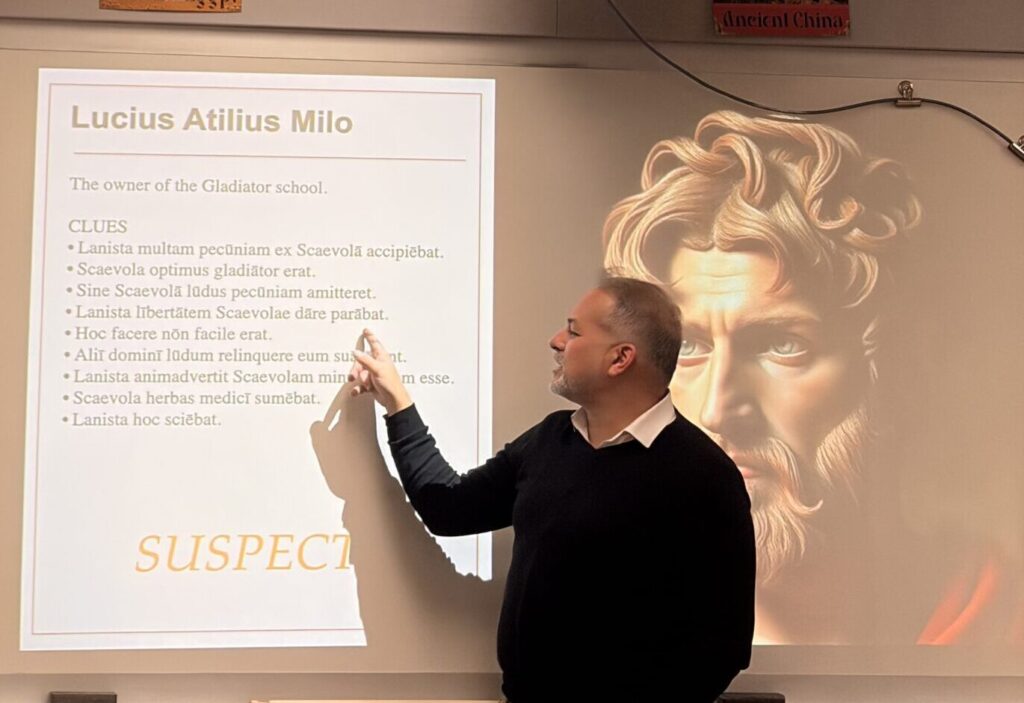

One way I ignite that spark with students is through a murder mystery I designed called, Murder at the Roman Baths, set at the Roman baths of Aquae Sulis, which is in modern Bath, England. The choice in settings offers one of the richest archaeological and epigraphic datasets in Roman Britain. Alongside monumental architecture and votive deposits, the site preserves over one hundred curse tablets—personal, fragmentary inscriptions that record conflict, theft, and desperation. This combination of material and textual evidence makes Aquae Sulis an ideal setting for an inquiry-based learning experience centered on historical reconstruction.

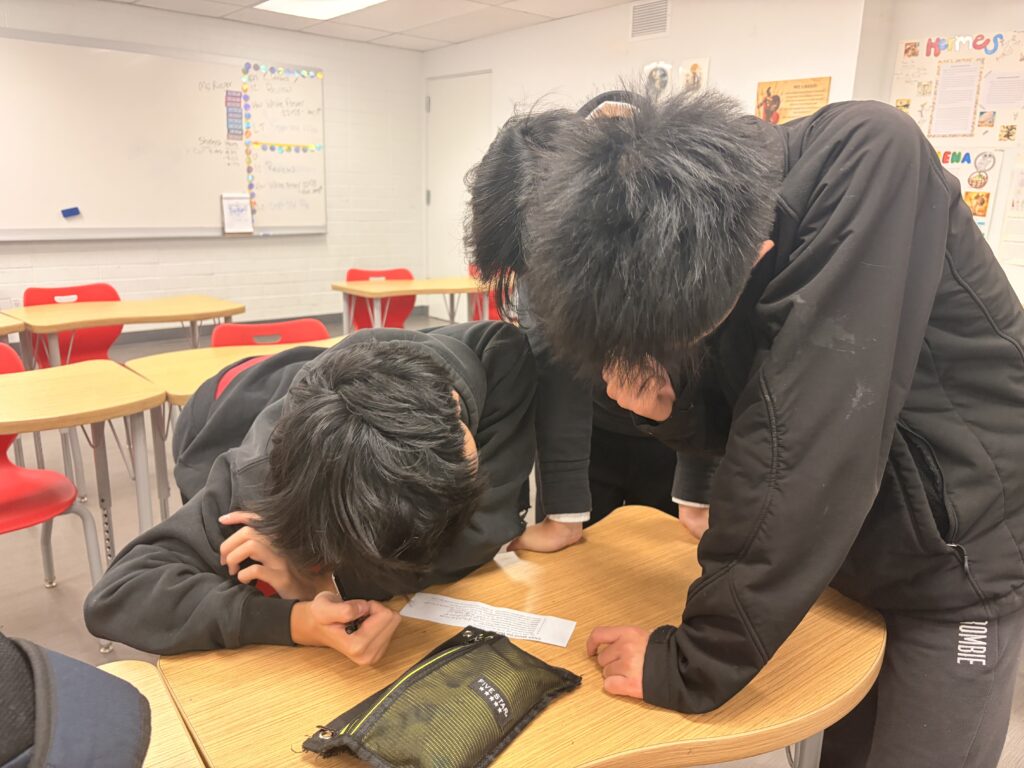

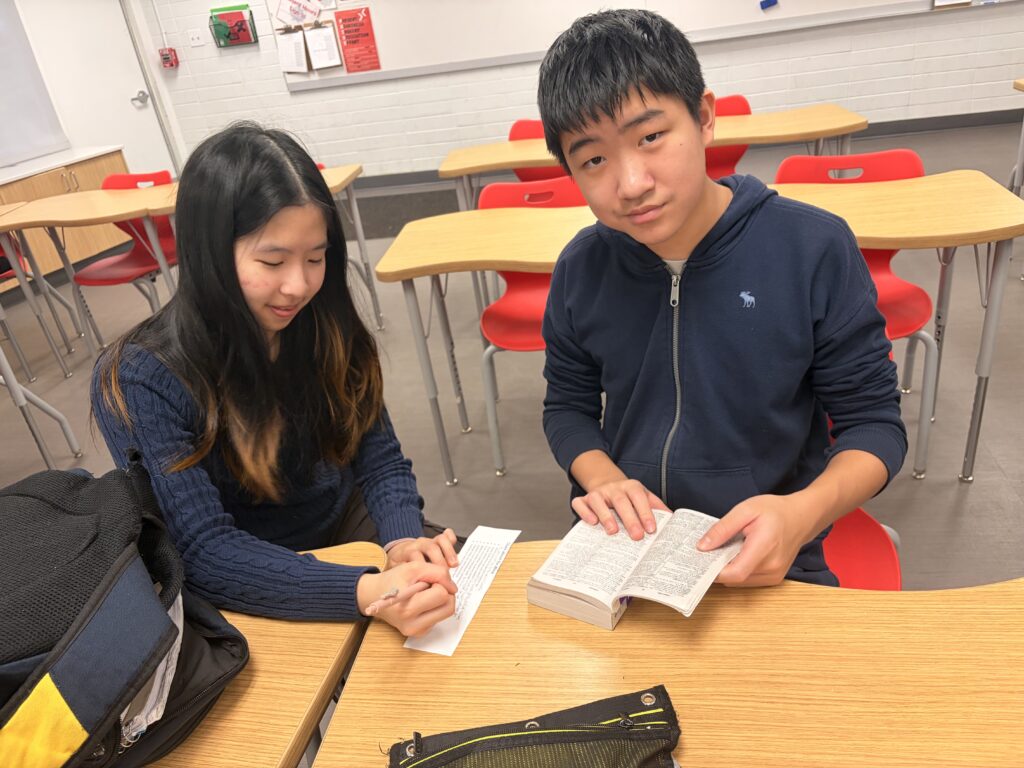

In this mystery, students have to investigate a fictional murder that occurred within the bath complex. Working as historical detectives, they are given a map, a list of suspects with their motives written in Latin, and make their way around the room to several stations in order to decipher Latin based clues. Students translate these clues from Latin to English and evaluate how these clues reflect personal motives that may fit with the suspect’s opportunity.

No single clue provides a definitive answer. Instead, students must weigh competing interpretations and build a plausible narrative grounded in what they know about Roman culture. Would a slave really “do in” their master? Suspects include desperate slaves, a rival merchant, a jealous wife, a friend who owed the deceased a debt, each one reflecting different aspects of Roman daily life, and therefore eliciting a student’s empathy.

Pedagogically, the mystery emphasizes both linguistic precision as well as historical reasoning. Who is most likely to have committed the crime. Translation becomes a tool rather than an endpoint, as students must decide how meaning, omission, and formulaic language affect interpretation. Archaeological evidence—the layout of the baths, patterns of votive deposition, and access to restricted spaces—provides constraints on possibility, reinforcing the importance of context.

The final product is a great example of how Latin can be made more relatable to students who presented with evidence, have to use their linguistic skills to uncover clues and defend a reasonable conclusion. This assessment prioritized reasoning over correctness, rewarding students who justify their interpretations with both linguistic and material evidence. The gamification of Latin and historical context in our bathhouse mystery helps transform the study of Latin from passive decoding into active inquiry, demonstrating how the ancient world can be reconstructed, maybe imperfectly, but at least persuasively, through careful analysis.

Why Latin Still Matters

Latin has a unique way of opening students’ minds. It trains students to notice patterns, think critically, and piece together meaning from fragments—whether those fragments are words, objects, or clues. Latin roots make English vocabulary clearer—especially in science, law, and medicine. Reading inscriptions teaches patience and creativity: how to piece together meaning from fragments. Studying Latin is not just about the past. It is about learning how to ask good questions, how to listen to overlooked voices—not just the emperors and the generals, but also the slave, the farmer, the baker, or the soldier who left a doodle on a wall before marching off to war, and how to uncover stories hidden in plain sight. It is not what I ever imagined Latin would lead me to in high school, and that sense of discovery is why I am so passionate about bringing this ancient language to life for my students each day.