Week 2 | Being Generous Is Bad, Economically??

March 16, 2023

This week, I began taking a look at which specific factors affect individual decision-making. I have come to a few conclusions:

- Reference Points And Relativity Matter People Tend To Focus On Reference Levels Instead Of Absolute Levels. For Example, Loss Aversion Explains How We Dislike Same-Sized Losses More Than We Like Same-Sized Gains (Even Though They’re The Same In Absolute Terms).

- There Is No Pure “Self-Interest” Sorry Adam Smith. If Everyone Was Strictly Looking Out For Self-Interest, No One Would Contribute To The Public Good. But The Thing Is, People Do. There Is, In Fact, Altruistic People!!

- Heuristics And Biases Cloud Judgement Hindsight Bias, Confirmation Bias, Mental Shortcuts, Reliance On Past Precedence… There’s Just So Many Instances Where We Think We Are Correct And Rational But Instead We’re Just Blinded By Our Brain.

IRL, many of us are not perfectly rational according to economic theory. We care about social preferences—about how other people/society perceive our actions. We care about how other people treat us—about the overall fairness of a situation.

That sense of irrationality explains why people tip at restaurants or donate impulsively to charity causes. Technically, you’re not obligated to pay. Especially if you’re at a random restaurant you’ll never visit again, there’s no economic reason for you to tip. But you still end up tipping. Because you care about how others perceive you and the social norm. Maybe you sincerely want to thank your server. Or maybe tipping makes you feel morally right and you receive a boost of serotonin and inflated ego. That’s up to you to decide.

Altruism

Alright, since my project is partially studying generosity and how that induces cooperative behavior, I feel obligated to define altruism.

There’s actually two different types of altruism:

Simple altruism is when people value the utility of others, even when it may cut into their own utility.

We can model it using this equation

U1(x) = (1- r) * Π1(x) + r * Π2(x)

(Rabin, 1998)

where U1(x) is person 1’s utility function, Π1(x) is person 1’s well-being from outcome x, and Π2(x) is person 2’s well-being from outcome x. When r > 0, that indicates how our concern for other people affect our own utility and thus decision-making.

The second type of altruism is impure altruism, or warm-glow giving. This occurs when people are altruistic due to the social implications of doing so, whether that is due to social pressures, fear of being judged, guilt of not giving, or any other psychological factor.

Warm-glow giving has been studied extensively in public goods games, such as those conducted by James Andreoni.

Public Goods Game

This week’s game is the PGG! Again, there’s many variations, and I’m just using my own numbers again :0

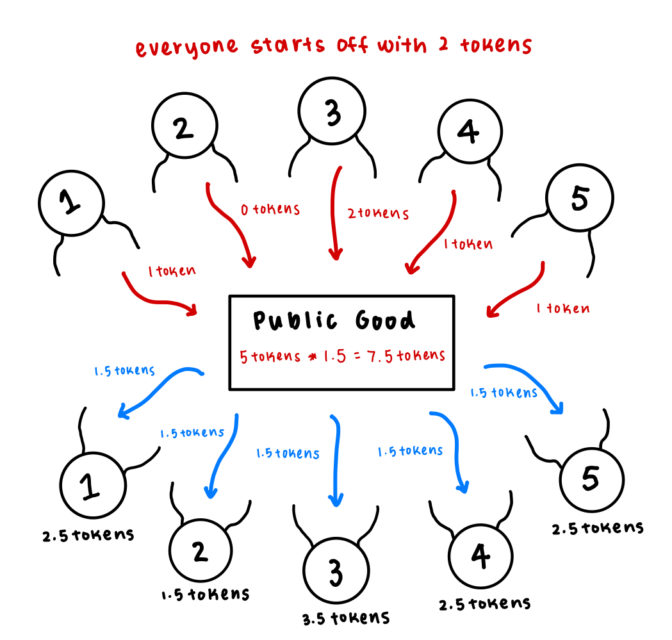

Assume you’re in a group with 4 other players. Each of you receive 2 tokens at the beginning of each round (5 rounds total). When prompted, all of you are given the choice to contribute any number of tokens to the public good. (This decision is kept anonymous and no one knows how much each group member has contributed!)

Tokens in the public good are multiplied by 1.5 and distributed equally among everyone in the group. Tokens not contributed to the public good are kept by each player in every round.

Shown above is just one example of a round.

How many tokens would you contribute? 0, 1, or 2?

Answer

According to Nash, you should always contribute 0 and free-ride off of other people’s contributions. However, in reality, people still contribute tokens, even in the last round of the game, when there’s actually no incentive to contribute anymore. In early stages of the game, you might want to contribute to build up trust.

As a result, PGG can be a great way to study generosity and cooperation. I was considering something like this for my study, but there’s just so many confounding variables and difficulties, ugh.

First off, the game requires a group, and that certainly makes participant recruiting a pain. I’d much rather have a one-shot game between two participants. Second, each round of the game presents a new scenario and potentially, a new strategy for each player to take. Third, there’s no way to directly measure whether generosity induces cooperation.

Anywho, I’m going to keep looking at game designs and bringing some of my findings to this blog.

Until next time,

Cindy

Sources

Andreoni, J. (1988). Why free ride? Journal of Public Economics, 37(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(88)90043-6

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Dawes, R. M., Orbell, J. M., Simmons, R. T., & Van De Kragt, A. J. (1986). Organizing groups for collective action. American Political Science Review, 80(4), 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.2307/1960862

Rabin, M. (1998). Psychology and Economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(1), 11–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2564950