Chapter 7: Uh-oh!

May 5, 2025

[You have 1 unread message.]

Hi everyone! Nice to be back. As you can see from my title, we have some…ummmm…interesting news…that I will share with you at the end of this blog post. But first, we’re diving even deeper into Schenkerian analysis, exploring some areas that we didn’t quite get to last time! I hope you guys still remember the bits of German we learned…you’re going to need it ;).

As a recap from our last chapter, Schenkerian analysis demonstrates (visually) how the basic Ursatz (the fundamental line) in the background (the simplest layer) expands to the complex, surface-level foreground through Auskomponierung (literally “composing out” or elaboration/prolongation).

Variation of Ursatz

Now, there are variations of the simplest Ursatz we looked at last time.

Developing from the background to the foreground, Ursatz can be prolonged in many ways, including but not limited to a tensional arch of initial ascent before the descending progression, motion from and to an inner voice, interruptions, register transfer, Mischung (mixture of minor and major).

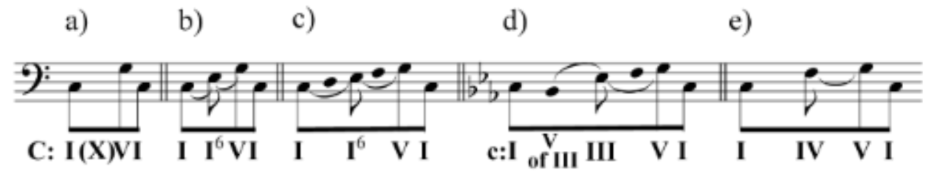

Because practically all pieces start and end with the tonic, Schenker proposes that the bassbrechung (literally translating to the “breaking” of the bass) has the common harmonic pattern of I-V-I. However, there are several ways that the bass can be “broken” and elaborated, notated by I-(X)-V-I (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Examples of I-V-I variations

Let’s look at an example of the Ursatz in practice.

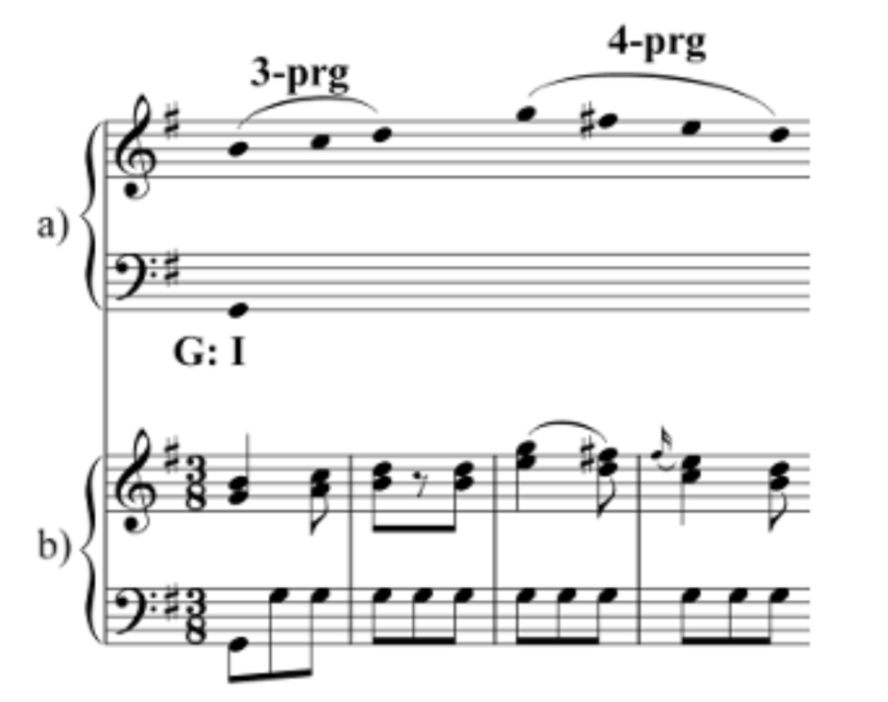

For Chopin’s Mazurka Op. 17, No. 1 (see Fig. 2), we can see the descending Urlinie from 5 to 1 and a bassbrechung that prolongs the I-V-I pattern. However, it is important to note that the notes (haha) of the Urlinie are not distributed evenly (Schenker’s ideas are not concerned with rhythm or timing).

Fig. 2

Elaboration

There are three main types of elaboration: 1) arpeggiation, a series of skips between notes of a single chord in the same direction; 2) Nebennote (neighbor note, see Fig. 3), a note above or below the original and is usually dissonant with the underlying harmony; and 3) Zug (linear progression, see Fig. 4), a stepwise motion between notes.

Fig. 3: Nebennote (labelled as “N”) from Bach’s Prelude No. 2 in The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1

Fig. 4: Zug (labelled as “prg,” or progression) from Mozart’s Sonata in G Major, KV 283, Presto

Of course, besides these types of elaboration, there are plenty of others, including Ausfaltung (unfolding), which skips back and forth between different voices, Ubergreifen (superposition/overlapping), which reaches over to transfer registers, and voice exchange.

Practical Application

Now that we have outlined the basic theories of Schenkerian Analysis, let’s take a look at the second movement from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in E Major Op. 14, No.1. To see the continuous unfolding of the Ursatz and the background.

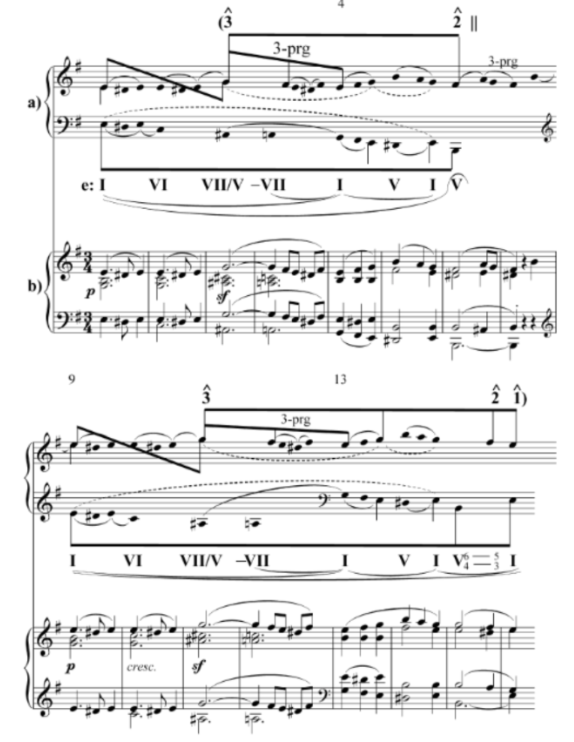

Fig. 5 shows an interrupted Urlinie descent from 3 to 1. E unfolds to G, which introduces the Kopfton (3, in this case). The prolongation of 3 continues until measure 7, and then transfers to the upper register in measure 9.

Whereas a traditional form analysis would show the various sections of the music in its entirety, a schenkerian analysis would interpret music in a single sweeping motion towards the ending of 1 with “obstacles, reverses, detours, expansions, nterpolations, and in short, retardations of all kinds” in between. A “retardation” would be, for instance, in measure 9 where the register transfers.

Fig. 5: Measures 1-16

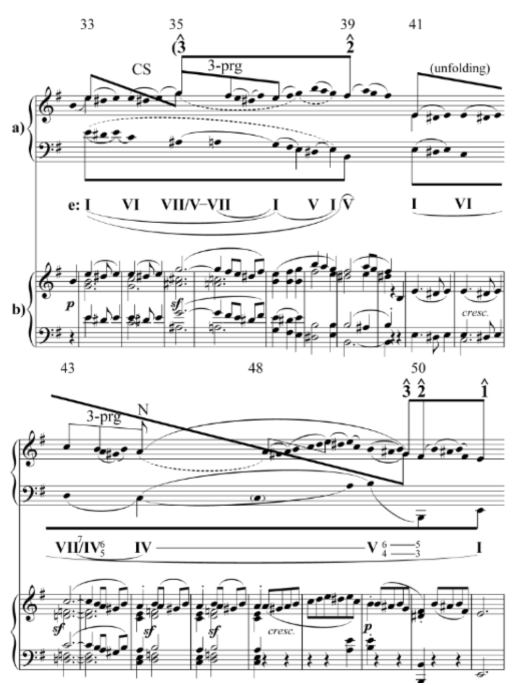

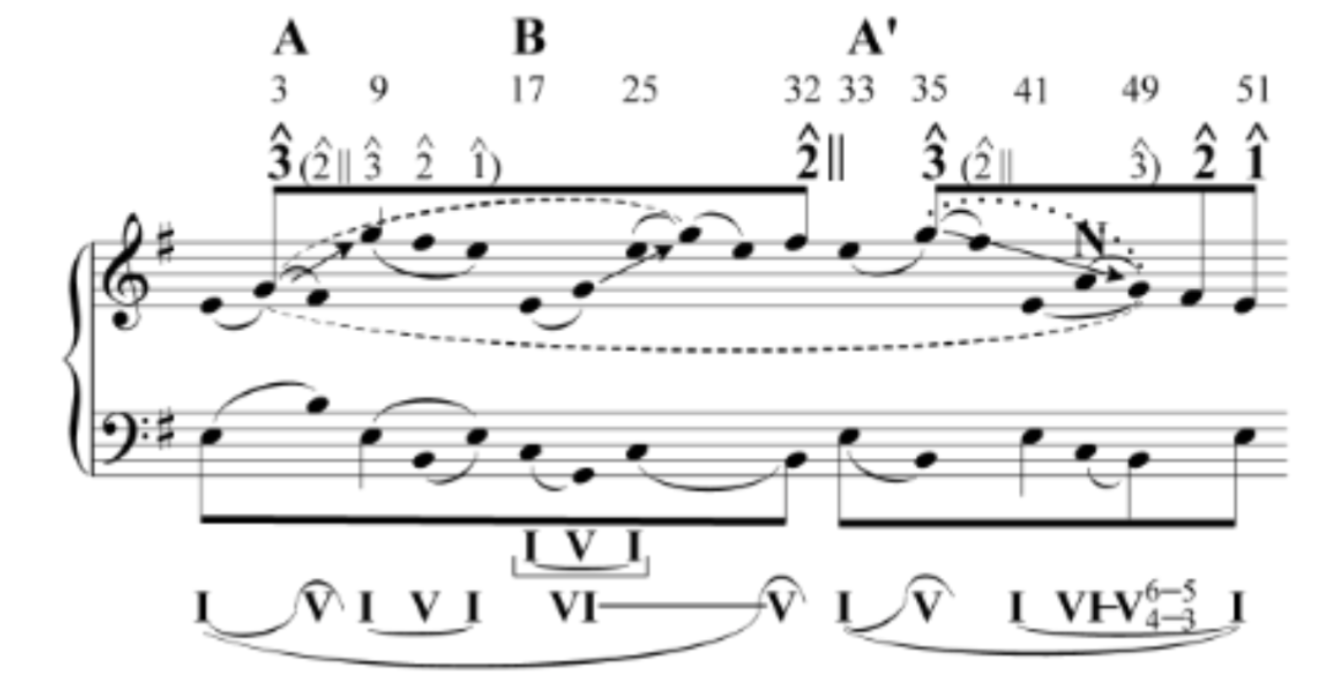

Interestingly, measures 33-51 (see Fig. 6) follow a similar trend. Besides starting in the upper register then transferring down to the lower register, the same basic Uriline is also an interrupted descent from 3 to 1.

Fig. 6: Measures 33-51

Below in Fig. 7, we see that the whole movement is unified into a singular pattern of two small-scale interruption structures with symmetrically balancing register transfers. That’s the gist of Schenkerian analysis.

Fig. 7

Seeing the piece from a Schenkerian POV is quite magical, but it also sheds light upon my own project. So now, apparently, there is a macro (or background) way of looking at my chord progressions and a micro (or foreground) way of looking at my chord progressions?!?!?

If you recall from two blogs ago, my advisor and I disagreed upon the chord progressions of The Story of My Life. And after reading about Schenkerian analysis, it turns out…that I was analyzing the song from the foreground—picking up upon the tiny details and the passing chords—while my advisor was analyzing the song from the background—just simply taking a big picture. Oh wow, things just get more complicated and more complicated…

However, I also realized through these readings…a major problem with my method: if I keep analyzing the foreground, I’ll pick up on unique details in every song, so each song would end with a slightly altered chord progression, so I can’t group my songs based on the chord progressions because I’ll get a different chord progression for each song!!!

Well, I guess time to re-analyze my songs, but from a macro-level. But first, I still have a little more reading to do next time! Phew, lots of work to do.

Sources:

Amarillo Vejiga. “SchenkerGUIDE: A Brief Handbook and Website for Schenkerian Analysis.” Academia.edu, 19 Feb. 2015, www.academia.edu/10929785/SchenkerGUIDE_A_Brief_Handbook_and_Website_for_Schenkerian_Analysis.

“Tom Pankhurst’s Guide to Schenkerian Analysis – What Is Schenkerian Analysis?.” Schenkerguide.com, 2025, schenkerguide.com/whatisschenkeriananalysis.php.

“Schenkerian Analysis (Explained for Beginner Musicians).” Producer Hive, 24 June 2023, producerhive.com/music-theory/schenkerian-analysis/.

“Schenkerian Analysis.” Wikipedia, 10 Jan. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schenkerian_analysis.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.