Chapter 6: Eine Neue Sprache Lernen

May 5, 2025

Hallo zusammen! Wie geht es euch? As promised last time, we will examine Schenkerian analysis! And judging by the title, I’m sure you have already guessed it, but we will be learning some German today!

What is it?

Developed by Heinrich Schenker, an Austrian musician and theorist, Schenkerian (wow, what an original name) analysis visually depicts the “layers” in a musical work. He proposed that musical works have three layers: the foreground, the middleground, and the background. In fact, if you are a big art person, you might already be familiar with these terms! Yep, he did adapt the vocabulary from the “foreground, middle ground, and background” in visual art.

Theories:

The background is the deepest and simplest layer that underlies all other layers, containing only a brief 2-line progression. The background then elaborates to varying amounts of middleground layers, which are essentially a semi-reduced score; these middleground layers increase complexity and details as you move towards the foreground, the outermost layer. The foreground presents itself on the very surface, containing all the intricate ornaments, complex details, and the teeny tiny aspects of the music (aka what we see on a music score).

Think of this like an onion: you see the outermost layer (the foreground), then as you peel, you will reveal more and more layers (the middleground and the background). And to boil it down to simpler words, Schenkerian analysis wants to reduce all the “fluff” as we get deeper into the musical layers.

Schenker’s theory revolves around the notion that all musical works are ultimately derived from a basic, fundamental structure in the background called the Ursatz. Although Schenker believed that the Ursatz is similar for all repertoire, Schenkerian analysis aims to demonstrate how the same Ursatz can be developed into the different, unique works we see in the foreground, giving it meaning. His motto—“semper idem, sed non eodem modo” (Latin students, it’s our time to shine!), meaning “always the same, but not in the same manner”—reflects the ultimate goal of Schenkerian analysis.

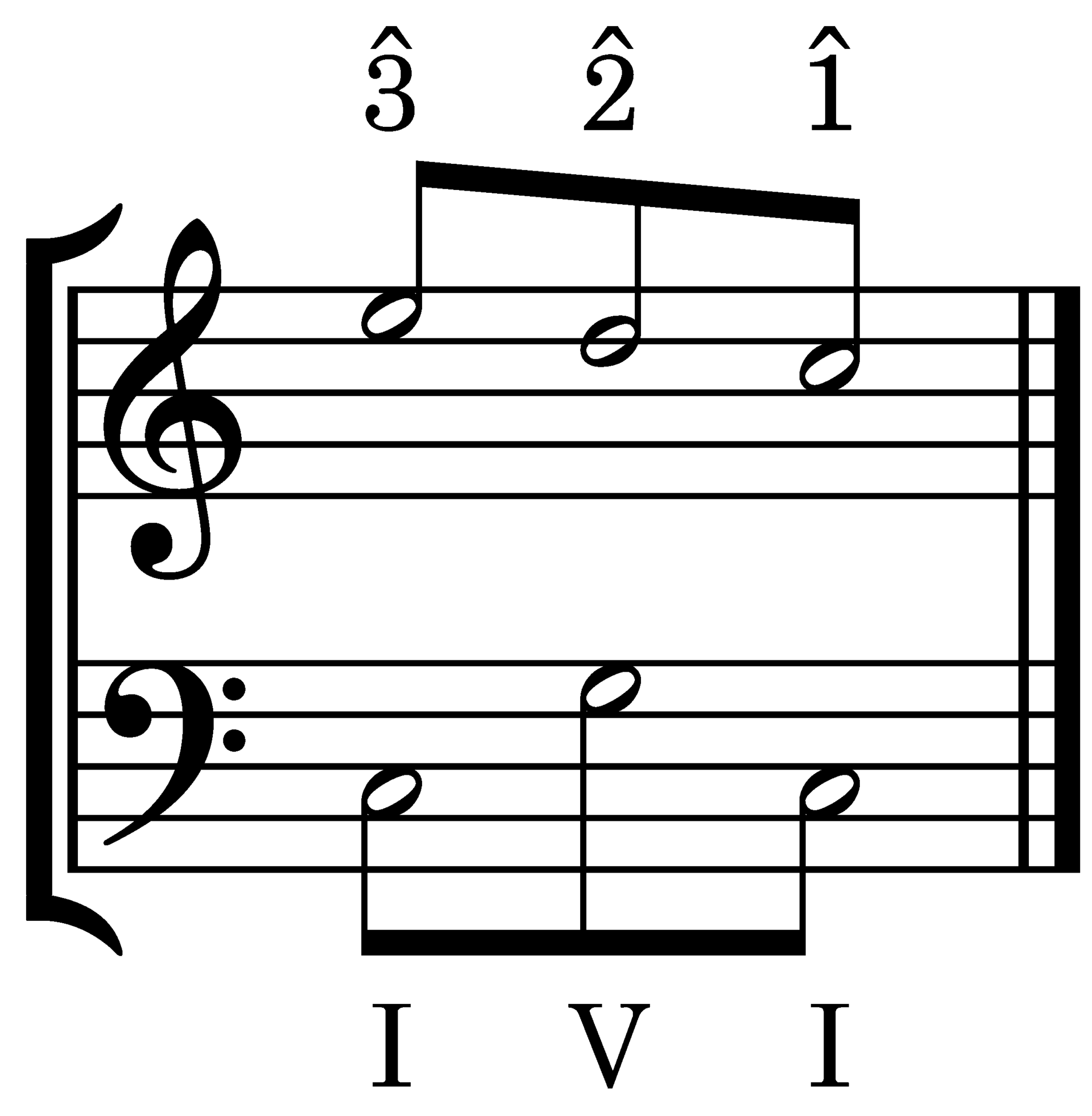

As Fig. 1 indicates, the structure of the Ursatz consists of 2 parts: 1) the Urlinie (the fundamental, main melodic line) must descend from one of the three possible Kopftones (head tones, or primary/initial tones)—3, 5, and 8—to 1; and 2) the Bassbrechung (the bassline) of the structure I-V-I should accompany the Urlinie.

Fig. 1: The simplest version of the Ursatz

For instance, the initial motif of Miley Cyrus’s “Flowers,” with the lyrics “We were good, we were gold,” has the three-note descending Ursatz that Schenker proposes.

We still have a lot to talk about, but let’s leave it here for now! Bis später (see you soon)!

Sources:

Amarillo Vejiga. “SchenkerGUIDE: A Brief Handbook and Website for Schenkerian Analysis.” Academia.edu, 19 Feb. 2015, www.academia.edu/10929785/SchenkerGUIDE_A_Brief_Handbook_and_Website_for_Schenkerian_Analysis.

“Tom Pankhurst’s Guide to Schenkerian Analysis – What Is Schenkerian Analysis?.” Schenkerguide.com, 2025, schenkerguide.com/whatisschenkeriananalysis.php.

“Schenkerian Analysis (Explained for Beginner Musicians).” Producer Hive, 24 June 2023, producerhive.com/music-theory/schenkerian-analysis/.

“Schenkerian Analysis.” Wikipedia, 10 Jan. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schenkerian_analysis.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.