CSA as Cement Replacement: Review of Previous Project, Project Direction, Data Synthesis/Analysis and Finding the Right Pan (A combination blog post)

March 3, 2024

Blog 1, Part 1: A Review of the Previous Part of the Project (Summer 2023)

For more information (and personal thoughts, technical aspects, background), visit my project blog site: https://itsjustmax.wixsite.com/maxseniorproject

Key Words:

CSA- Coconut Shell Ash

Concrete- Ordinary Portland Concrete, made of cement + water + aggregates (rocks, sand)

SCM- Supplementary Cementitious Material

ASTM- ASTM International, formerly “American Society for Testing and Materials”

SEM- Scanning Electron Microscope

Cemex- International concrete company (https://www.cemex.com/home)

Fortera- Smaller sustainable concrete company (https://forteraglobal.com/paving-the-way/)

A Review of the Previous Part of the Project (Summer 2023):

In 11th grade, I wanted to try using agricultural SCMs* (Supplementary Cementitious Materials) to partially replace cement in concrete (since cement production creates massive carbon emissions inherent in the chemical reactions), and after searching online for days, the only agricultural SCM I found available in larger quantities was Coconut Shell Ash (CSA).

Then, I cold-called/emailed various professors/companies seeing if they could help me create concrete mixes. The reason external help was necessary was that the concrete industry uses very specific ASTM standards with special equipment (some of which can be seen below) that can be expensive/difficult to procure. Miraculously, when I visited Cemex’s San Jose office out of desperation, I got in contact with my current advisor, Nick (now at Fortera), who set me up with Eric to make concrete samples at 15, 25 and 35% replacement of cement (by weight) in the concrete, along with normal concrete ingredients like small, medium and large aggregates being added in. The compressive strength of the concrete cylinders created was tested with hydraulic press at 7, 14, 28, and 56 days after making the concrete. Concrete usually gains strength over time, gaining strength up to months after mixing.

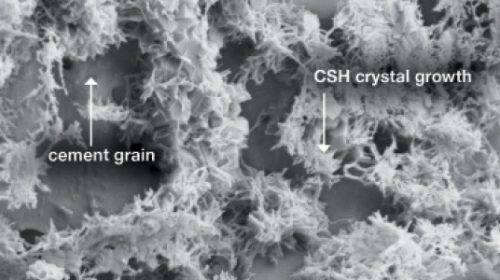

*Note: SCMs work (usually) by containing Silica (SiO2) and/or Alumina (Al2O3) and participating in pozzolanic reactions, which are complex reactions that pretty much work to create a strong “CSH” chemical network that adds strength to the concrete.

(Making concrete mixes at Cemex, Summer 2023)

(Making concrete mixes at Cemex, Summer 2023)

(CSH crystal network in concrete, from https://concreteproducts.com/index.php/2018/03/19/basf-agent-propagates-csh-crystals-to-increase-early-late-age-strength/)

Summary of Key Findings/Results from the First Part of Project:

A. As seen below, oxidation was caused on the steel shrinkage test molds, with oxidation increasing with CSA concentration.

-

This is very rare for SCMs, and is also very bad because concrete is often used with steel reinforcement (to add tensile strength), and corrosion of steel can degrade/weaken the steel. Cemex told me that any material that oxidizes steel won’t do well in the industry

-

Potential Solution(s): Using a powerful magnet to extract iron chunks (seen in Scanning Electron Microscope images) and using a chemical wash to purify the ash.

(oxidation of steel shrinkage molds caused by CSA concrete)

(oxidation of steel shrinkage molds caused by CSA concrete)B. As seen in the graph below, compared to the similar Rice Husk Ash concrete (graph from literature in Figure 5), the Coconut Shell Ash concrete I made (data in Figure 4) had significantly lower strength, especially as replacement percentage increased.

- Through “back-scatter” chemical analysis of the CSA at Fortera, we saw that a large portion of the CSA was actually carbon (with plants like coconut being largely carbon-based), and since carbon does not really contribute to the concrete strength, as we added more, strength decreased.

- Solution: Using controlled burning in an oven (at 600-900 C) to burn off some of the carbon, leaving a higher proportion of silica and alumina and calcium (which contribute to strength). The key (and problem) is balancing burning time, as burning for too long of course will emit more carbon and use more energy, both un-environmental things to do.

(Top graph: my compressive strength data with CSA concrete over up to 28 days. Bottom graph: literature data of Rice Husk Ash concrete compressive strength up to 56 days)

(Top graph: my compressive strength data with CSA concrete over up to 28 days. Bottom graph: literature data of Rice Husk Ash concrete compressive strength up to 56 days) (Back-Scatter chemical composition data of raw CSA)

(Back-Scatter chemical composition data of raw CSA)Blog 1, Part 2: Project Direction: An Overview of the Months to Come

As of last week, work has gotten underway on the current phase of the project.

Already, there have been changes to the original project syllabus/plan due to confirmation/changes in timing of essential events:

First of all, burning of Coconut Shell Ash (CSA) has begun on a 25 kg batch of CSA from the previous part of the project, but we wanted to order 50 kg more of CSA, since we’ll be burning off carbon until around 50% in weight of the CSA is left (doing the math, (25+50)*50% equals around 37.5 kg of CSA left). This much CSA is needed for making numerous test cylinders for strength testing (3 cylinders each for the 4 testing times of 7, 14, 28, and 56 days, times the 3 different weight percentages, a total of 36 cylinders) and for miscellaneous small-scale lab-testing.

Unfortunately, burning is constrained by both the size of containers for the oven, and by the shipping time of the material from China. Not only that, but we had to order 60kg of CSA this time since the supplier only sells in bags of 20kg now. This is sure to incur a massive shipping cost if we want to ship by FedEx plane, so I also need to find a job to pay for all of this.

I also contacted Cemex, and Eric said the earliest we could make the mixes of concrete was 3/21, so I swapped the plans around to do more literature review now rather than later. We may also not get the 56-day test results before presentations, but the 7 through 28-day results usually give a good idea of results anyway.

To Summarize the Important Parts of the New Senior Project Plan:

The project will consist of 3 parts still:

Part 1: Burning of the Coconut Shell Ash, although time will be extended more than 2 weeks initially projected (perhaps)

Part 2: Lab testing at school to test other properties, such as geopolymerization (using alkaline liquid to “activate” the material, creating a cement with 0% actual cement). I’m still finalizing ideas, but I believe washing the CSA with strong bases and acids before making concrete could have interesting results as well.

Part 3: Literature review with comprehensive data analysis. This has already started and will likely continue throughout the long concrete-making process. I hope to use SCM (cement replacement/supplements) abundance data (how much of each type is made and where), economic data (such as costs and tariffs/trade) and other factors I find while researching and reading numerous articles. This will help determine the future of the SCMs market in general, and the future use cases of CSA specifically. The important part of this part is summary and visualization for ease-of-use by other researchers or readers.

It appears that this summary was as long as the first part, but I hope you see that I want this project to be an intersection of my scientific and humanity interests, under the umbrella of solving environmental issues. The climate crisis is not an isolated issue; it affects all parts of our society, and it’s time to start treating it like that when we try and find solutions to this massive issue. Let’s all start trying to think outside the box when considering environmental issues!

Blog 1, Part 3: Data Synthesis: Analyzing the SCM Supply

The SCM Data/Literature Review Process

Since it seems that the burning of the CSA (Coconut Shell Ash to partially replace cement) is taking longer than expected (more on that in another post), and Nick at Fortera is kindly burning the CSA at around 800-900 Celsius for me, I’m using my time to start analyzing how the supply of coconut shell ash stacks up. Below are the results so far, using the most recent and reliable data I could find to make these graphs.

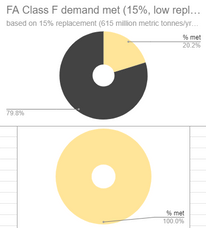

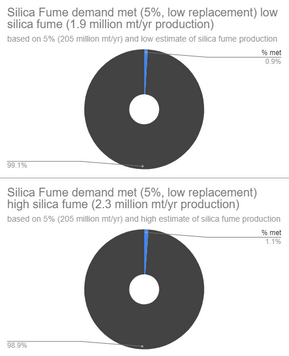

The pie charts show, if (theoretically) SCMs replace cement (by weight) at literature ideal replacement ranges, for all cement, then what percentage of that overall replacement demand could the (theoretical) world supply of that replacement meet (per year). I created pie charts at the lowest and highest % replacements for the SCMs, so the real % of demand met is probably in-between what I have. For some SCMs, there were also an estimate range of yearly production, so I also used the highest and lowest production estimates to create two graphs.

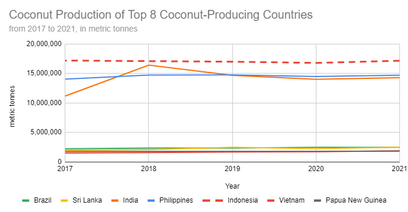

So far, I’ve covered the SCMs: Fly Ash Class C, Fly Ash Class F (both from coal burning), Silica Fume (from silicon/ferrosilicon production), and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) from iron manufacturing. These are the most common SCMs and are generally waste material. You can also see in the Coconut Production graph that I’ve started looking at how CSA stacks up to these other common SCMs.

(a small section of my complex google sheet data)

(a small section of my complex google sheet data)

The calculations were a bit complex, so here’s an example of how I did them:

If we make 4,100 million metric tonnes of cement per year, and we wanted to replace 25% of that with Fly Ash (FA) Class F (25% is the high estimate of ideal replacement percentage of FA Class F with cement), then we would need 1,025 million metric tonnes of this FA Class F per year to totally cover that demand, but we only make around 740 million metric tonnes of FA Class F per year (2022 data), therefore, (740 million mt/yr SCM made) / (1,025 million mt/yr SCM needed) x 100% equals 72.1% of this theoretical demand met (as seen in the top right pie chart below).

(FA = Fly Ash from coal production, Silica Fume is from silicon/ferrosilicon production, GGBFS = Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag from iron production)

Calculations and Complications

The data hasn’t always looked this good, in fact, I had to scour many sources, such as the US mineral and commodity summaries (for production numbers), Our World in Data (for coal usage in different countries) and various research papers for how much SCM is produced from the production of these products (per metric tonne). I also had to separate calculations based on 1) Varying production estimates and 2) Different percentages of replacement of cement by that particular SCM.

(For the Fly Ash, I had to take coal power production and convert that to coal usage then convert that to how much of each type of fly ash (C or F) was produced. It was mind-boggling)

Even after all of this, my data is only a relative estimate, since there are other factors not considered such as 1) Amount of the SCM used for non-cement-replacing uses (asphalt, bricks, etc.) and 2) The amount of cement already being replaced by the SCMs, as SCM use is fairly commonplace already. 3) There are other circumstances such as not all the SCM being captured (like Fly Ash in Chinese coal plants) or collected/sold, and certain locations not being able to access SCMs (due to distance and/or politics). In general, this means that the actual usable supply of SCMs is likely significantly lower than my estimated demand percentages met, but I think they still tell something about how the SCMs stack up compared to eachother. For example, we can still tell that iron and coal production still meet much more of the SCM demand than silicon production.

My Plans for More Data Analysis/Comparisons of SCMs

I plan to continue this data search/summary with agricultural SCMs such as Rice Husk Ash, Palm Oil Fuel Ash, Sugarcane Bagasse Ash, and of course, Coconut Shell Ash (CSA) itself, as these are all plant-based SCMs similar to CSA. After, I plan to investigate the costs of the SCMs.

In general, this work is important because the cement/concrete industry is so massive (remember: 4.1 billion tons of cement made per year) that production numbers and money matter a lot. Even if the science is sound (which I’m investigating later), these other factors can still render certain SCMs useless if they don’t meet industry demand.

Blog 1, Part 4: Searching for a Suitable CSA-Burning Container

The Background

Nick from Fortera is thankfully helping me burn the 25 kg batch of CSA leftover from the previous part of the project (and later the 60 kg batch being shipped over from China) at around 800-900 Celsius (my oven at home would probably not reach those temperatures). The reason behind the burning is to reduce the carbon (and other impurities) in the CSA until it’s around 50% of the original weight (3-4 hours of burning). Unfortunately, Fortera only had small ceramic trays and crucibles that could resist the high temperatures necessary, so it was up to me to find larger containers, or our rate of burning would be around 3-5 kg per week, and we would miss the March 21st deadline for making concrete at Cemex.

The Search

As most searches for products, my searched began on amazon and google shopping. Unfortunately, my searches for “containers for high temperature applications/burning” only yielded lunch containers made of weak metal, glass and plastic. I needed large containers that could handle my intense project. After a few hours of clueless searching, I asked Nick for advice, and he told me to look at strong stainless steels, ceramic and perhaps graphite. Searches for ceramic containers yielded plant pots (too small or tall) or ceramic crucibles (pictured below). Searching for Graphite containers, I found scientific-application crucibles that costed an arm and a leg (also pictured below).

So… I decided to look outside, and visited Clay Planet, a pottery shop, to see if they had any products or useful advice. John, a helpful pottery veteran who only worked at that location on Saturdays, suggested a few clays that could be up to the job, but also said we might have to get our container custom-made to our specifications. John also suggested that CSA could have pottery applications, similar to other natural ashes such as volcanic ashes (used in glaze formulations). I would love to explore this use of CSA if I have the time.

Still confused, I returned home and consulted my trusty friend and coworker: my dad. He suggested I look at lab equipment sites such as Fisher Scientific. At the same time, I was also researching grades of stainless steel, as that seemed promising. Turns out 300-series stainless steel has high temperature resistance, up to 870-1000 Celsius. Therefore, I narrowed my search to stainless steel containers on these lab equipment sites. Finally, I found … nothing useful. Actually, we had one lead for 304 stainless steel containers, but upon contacting the seller, they said they only sold to other businesses.

Then, when all hope seemed to be lost, my dad suddenly remembered that he sourced many materials and equipment from an online supplier called Mcmaster-Carr. We looked and found dozens of 304 and 316 (even better than 304, with heat resistance up to 1200-1300 Celsius) stainless steel trays, ready to be shipped in a day or two. Sometimes, the answer is right under your nose all along, you just have to be willing to speak to and work with the people around you. We ordered 4 and they will arrive at my house early next week.

Thanks for reading this far, I hope to have good news on the burning next week!

-Max Polosky

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.